the recipe file

Well, it’s about the most fun you can have with a stack of 3 1/2 x 5 index cards. Last week I opened, really for the first time as a serious cook, my grandmother’s recipe collection which I inherited when she died. It’s an enormous stack of yellowed, torn, spilt-upon treasures, but treasures in not exactly the way you might think. There is almost no chance that a modern person will want to cook anything described in these cards, but that is really beside the point.

Well, it’s about the most fun you can have with a stack of 3 1/2 x 5 index cards. Last week I opened, really for the first time as a serious cook, my grandmother’s recipe collection which I inherited when she died. It’s an enormous stack of yellowed, torn, spilt-upon treasures, but treasures in not exactly the way you might think. There is almost no chance that a modern person will want to cook anything described in these cards, but that is really beside the point.

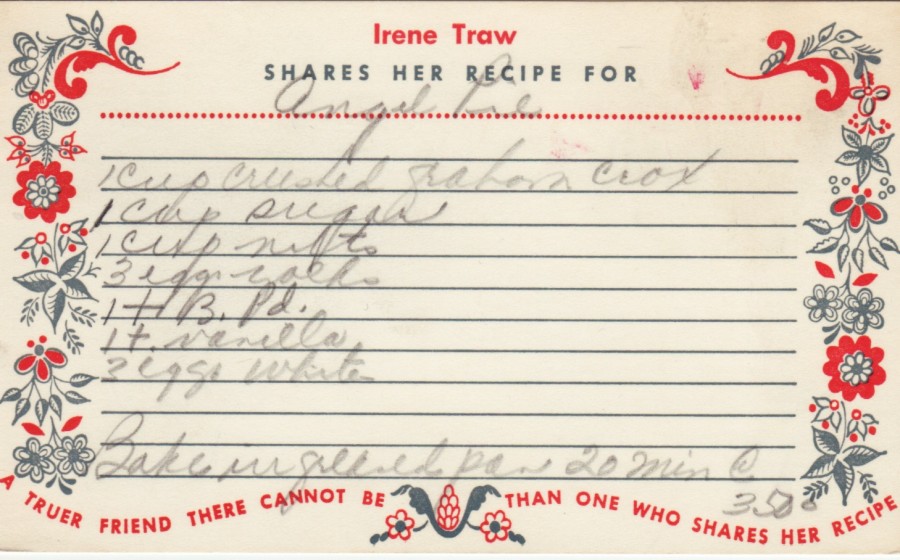

What emerges from these cards is a picture of a life gone by, on many different levels. Only a portion of the cards comes from my own grandmother’s kitchen; the vast proportion of them are gifts to her, from ladies (and I mean exclusively ladies, which is a topic all its own) in her intimate circle. One Irene Traw passes along her notion of an “Angel Pie,” a frothy concoction of separated eggs and graham cracker crust, on a dear little card bearing her name and the legend, “A truer friend there cannot be than one who shared her recipe.” My mother remembers Irene vaguely as a bridge-playing crony of my grandmother’s, in the posh retirement community of Sun City, Arizona, where she and my besotted grandfather moved when I was a little girl. Irene, Ruth Pentecost, Evelyn Adamy, Betty Joy, the nameless lady who took the time to cut out magazine pictures of sunflowers and glue them to her recipe card containing instructions for “Fudge Cup Cakes Supreme,” all these ladies emerge from the dusty cards, wiping their hands on their aprons and smiling at me.

These ladies inhabited a world in which brides-to-be were given personalized recipe cards on which to note down their creative efforts (woe to my poor mother who must have looked at her cards with a sense of impending doom, as her creative efforts were more likely to find an outlet in embroidering samplers than in separating eggs). I suppose then they ate at each other’s houses, admired Ruth’s “Molded Fish Mousse” (a name that had my modern daughter rolling on the floor laughing) and asked for the recipe. And of course they were all ladies, not a Sam or Cyrus among them, and this fact brings out in me the little bit of feminism that says men may be (and are) great chefs, but the really important stirring and mixing, boiling and chopping in this life is done by ladies.

Were these the early Ladies Who Lunch? Only instead of paying for Gordon Ramsay to wow them with foie gras parcels and confit of duck leg in a Jerusalem artichoke veloute, they fed each other at home, maybe potluck style? Each lady would surely arrive armed with a dish designed to impress. During the endless hot, dry afternoons in the desert, they would light their inevitable cigarettes and begin with Ruby’s “Crab on Holland Rusk” (what is a rusk?), followed by Miriam’s “Pistachio Pie” (containing no pistachios, and also presentable as a salad, the recipe assures us). It must all have been washed down with “Invitations to Love,” a potent-sounding concoction of lime juice, orange juice, vodka, apricot brandy and grenadine. A few more cigarettes, a couple of hands of bridge and then home, to concoct “Shrimp Dish,” from the kitchen of Sally Johnson, for their husbands, fresh from the golf courses and their own three-martini lunches.

Sally Johnson’s Shrimp Dish

1 pkg. Uncle Ben’s long grain and wild rice mixture

1 can mushroom soup

10 oz. pkg frozen cooked shrimp

1/2 cup cubed American cheese

2 tbsps green pepper, chopped

1 tbsp lemon juice

1/2 tsp Worcestershire sauce

1/2 tsp dried mustard

1/4 tsp black pepper (no Salt though)

Prepare rice as directed on package, combine all ingredients and bake in covered greased dish at 375F for 30–35 minutes. Serves 6.

Try this by your swimming pool.

*****************

This last instruction stopped me in my tracks. Maybe with an exclamation mark it would have read in a different way, “Try this by your swimming pool!” That would have conveyed a nice, celebratory atmosphere with plenty of cocktails and dark glasses. As it is, it sounds slightly threatening. This impression was underscored by my mother’s assurance that my grandparents did not have a swimming pool; they swam at the community pool. Was the author of this recipe throwing her obvious possession of a pool in my grandmother’s face?

My great-aunts Andrine, Rae and Hannah (who I grew up thinking was not Aunt Hannah, but “Antenna”) are present and accounted for in many recipes in my grandmother’s file, as is my father’s cousin’s mother Miriam, with recipes for Eagle Brand Pie, Oatmeal Refrigerator Cookies, Hot Ham Strata, and something called Flintstone Dip. All the recipes share one thing in common: an unspoken but intense frugality of ingredients. No savory recipe seemed complete without a can of Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom Soup; it seemed to be a sort of universal lubricator of such diverse items as bacon, spinach, hard-boiled eggs and canned lima beans. Almost nothing in these recipes started out life fresh: spinach was frozen, milk evaporated and canned, tomatoes juiced, red peppers suspended in vinegar and called pimentos. Even the main dishes were manipulated. What was not casseroled was molded, stewed or formed into a loaf. Not for my grandmother and her friends a simple fillet steak, roasted chicken or pork tenderloin. As my mother explained, these ladies had a mission, first in their post-war poverty and later in a state of habitual frugality, to eke out the expensive proteins in their diet with cheap and filling starch, and to change its original appearance as much as possible to achieve something special from something very ordinary indeed.

To this end, vegetables (never fresh to begin with, even celery was canned) were mixed with gelatin, covered with a white sauce, braised in chicken stock from bullion cubes, mixed with frozen fruit and flavored with an endless array of mysterious seasonings. Dips were made to accompany bread chunks or cocktail sausages at parties, their mayonnaise (or even cheaper, Miracle Whip Salad Dressing) flavored with Lowry’s Seasoned Salt, Lipton French Onion Soup Mix, Accent Seasoning (its only ingredient being monosodium glutamate) or Beau Monde seasoning which combined a motley array of both sweet and savory spices. There was even a condiment called Liquid Smoke, which imparted a charcoaly (and no doubt carcinogenic) flavor to meat dishes. And you know what I just realized? In all these hundreds of recipes, there is no mention of garlic. Do you suppose it was too “foreign”?”

One recipe stood out for me among the many cookie recipes, “Jewish cookies.” In the margin of my grandmother’s recipe card was the notation, “A favorite of Bert Weiss.” Surely they could not be called “Jewish Cookies” just because someone named Weiss liked them? Even for my very Protestant grandmother this could not be true. I read the list of ingredients, looking for pastrami or matzoh meal or brisket (in this pile of recipes, anything was possible), but there were only the most ordinary items like flour, butter, eggs, shredded coconut, orange marmalade. When I read this recipe out to Avery, however, she promptly said, “Oh, those are hamantaschen, a traditional cookie for Purim. It’s the marmalade that tells you that.” I thought back to Purims in New York with my friend Alyssa, who made them with apricot jam, I think, and blessed my daughter’s ecumenical wisdom. But did my grandmother know the rather obscure food traditions for one of Judaism’s less famous holidays? I wish, as I have wished so many times holding her recipes on my lap, that she was here to ask.

When I think of the way I cook now, buying several fresh ingredients for every supper and always cooking more than the three of us need (and inordinately proud of myself for using leftovers even most of the time, certainly not all), I am ashamed of my profligacy. Tonight’s supper will be fresh sea scallops sauteed with garlic and tons of flat-leaf parsley in a sea of extra virgin olive oil, to be served with spaghetti and breadcrumbs made from my own homemade focaccia. It’s shameful! I have probably spent my grandmother’s entire food budget for the week, even the month, on one supper.

My grandmother was a very difficult person. She was a rather mean mother, a demanding wife, a critical and unloving mother-in-law, a self-centered and for the most part uninterested grandmother. Her infrequent visits to us were fraught with tension that my rather gentler grandfather tried to defuse. Nothing was ever good enough for her and in fact was very much not to her liking, and she told us so. But she brought us raisins from grapes she and my grandfather had picked in the Arizona fields and dried on white bedsheets in their backyard, and she let me watch as she made a yeasty, cinnamony tea ring studded with their chewy goodness. In their front garden, she picked kumquats for me and laughed as I tasted the bitterness, and was grimly proud when I liked them. She taught me, both at her knee on our very occasional cooking afternoons, and also I now think through the mysterious gift of genetics, to love food and cooking. And if Irene, Ruth, Betty, Evelyn and the dozens of other Ladies Who Lunched are any indication, she loved her friends, and they her.

I must find a box for these cards, every one of them bearing the handwriting, and behind that the personality, of a lady. It’s what I’ve always believed about food, and what my own motley collection of recipes will prove about me. To cook for those you love, and to share your recipes with them, gives you just that little piece of immortality on someone’s desk in faraway, foreign London.