What happened to us

On September 10, 2001, we got up early in our Tribeca apartment because it was the first day — only a half day, but still, the first day — of kindergarten for Avery.

I pretended to be as excited as she and John were, as she burbled on about finally being in “real school,” about her new shoes, about finally, the next day, staying in school to eat her lunch.

I, on the other hand, had spent the entire summer thinking I was dying of something. Not sure what, but sure something was drastically wrong with me, I haunted doctors. I went to my GP several times, who promised me, “You’re fine, and even if you’re not, whatever it is, we’ll fix it.” From there I saw a gastroenterologist, an endocrinologist and was about to see a neurologist when something eye-opening happened to me. I picked up Avery at summer camp one afternoon, and realized that all my symptoms- a pervasive stomach-ache, slight tremor in my hands, rapid heartbeat- disappeared as soon as I had her hand in mine. I went home, tore up the reminder for my appointment with the neurologist, and set myself to the task of learning to say goodbye to my little girl, to leave her at school like all other parents leave children at school. I was suffering from pre-separation anxiety, not a brain tumor.

That first half-day of school I felt like the world was coming to an end. Since she was a baby, Avery had gone to “preschool,” a sweet little Montessori morning activity with her best friends Cici and Annabelle, trying to become socialized, to let other people talk, to share, all difficult tasks for an adored only child both of whose parents turned instantly toward her the moment she opened her mouth. I knew that all-day real school would be even better for her. She had never looked back for me when I left her at preschool, only turning resolutely toward her real life, happily leaving me behind. I was the one with the problem.

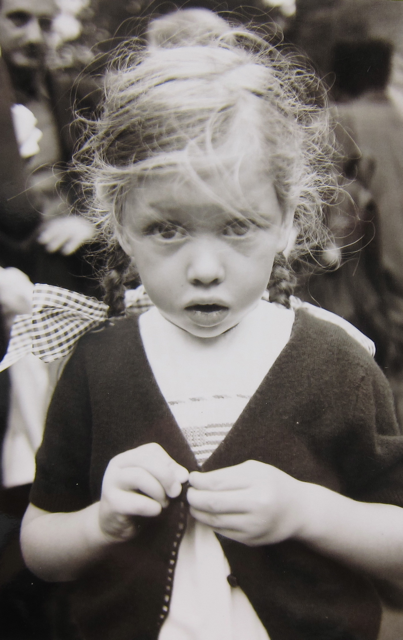

John and I took her to school, or rather she took herself, that first half-day of kindergarten, bouncing down the sidewalk with Cici, who lived in the same building with us. They could not have been more excited. She was so adorable, so pure and priceless, that we took lots of photographs. Here she is outside the gate, wearing the special new outfit she had planned for days. Especially the beret.

And the red shoes, which made little clicky sounds on the sidewalk as she skipped along.

And the red shoes, which made little clicky sounds on the sidewalk as she skipped along.

Into the school she went. I spent the morning trying to think of what I was going to do with my year, what every parent thinks of as the year from September to June. I had quit my teaching jobs the last year in order to write a book, and it was nearly finished, only waiting for museums to give permission to use their images. It would keep me busy.

Into the school she went. I spent the morning trying to think of what I was going to do with my year, what every parent thinks of as the year from September to June. I had quit my teaching jobs the last year in order to write a book, and it was nearly finished, only waiting for museums to give permission to use their images. It would keep me busy.

The half-day ended and I went to pick her up in the little concrete schoolyard surrounded by the wrought-iron ornamental fence, a fixture in our neighborhood. It was a coveted school, that rare thing: a New York public school that was safe, supported by parents, cozy and successful. I was surrounded by other mothers, by fathers and nannies, waiting for the children. The sky was dark with heavy clouds, the air so humid it pressed against our faces like a wet washcloth, tiny drops of rain began to sprinkle onto our heads. Suddenly there was a CRACK, a shocking CRASH. We all jumped a mile high, then looked sheepishly at each other, laughing at our silly panic, as the heavens opened and the afternoon dissolved into a thunderstorm.

At last the doors opened: the big front door to the school where the older children came out, and the little red door onto the schoolyard where the little ones were shepherded out by their loving teachers. And there she was. “I LOVE Abby! She is the nicest teacher! And we colored, and we’re going to be studying chicks! And how they turn into chickens!” Avery’s words tumbled over each other as I picked her up, a feeling of deep relief showering me, lowering my blood pressure, making me sigh with happiness. Everything was going to be FINE. Why had I dreaded school so much? She had had a wonderful morning.

She was so earnest, so concerned about fitting in and doing the right things.

She was so earnest, so concerned about fitting in and doing the right things.

That night the clouds rolled out, the temperature dropped to a perfect September nip. The next morning, the first full day of school, dawned famously blue and perfect. I don’t have to describe it because it is its own category of day now, “a September 11 kind of day.” It was the second day, so no more fancy clothes. She put on a yellow t‑shirt and a little full skirt with appliqued pink and orange fluffy flowers on it. John didn’t come with us. Having his own life to attend to, he headed to work in Times Square and I headed down the three blocks between our apartment and the school, handed her her lunchbox (Hello Kitty), gave her a hug and kiss. “See you at 3 o’clock!” I said, and watched her cavorting in the schoolyard with the children who were already her friends. We were early. It was just after 8:30 a.m.

I caught up with a mother I recognized as having a little girl in kindergarten, and we walked together uptown, she pushing her little boy in a stroller. “Jen, are you at all nervous or upset at Tova’s going to school all day?” I asked, feeling foolish but as usual wanting to see if someone else shared my experience.

“Are you kidding, with this little guy to entertain all day? I’m thrilled,” she said. We went on chatting.

“What? What did you say?” I shouted.

“I can’t hear you either,” she said, and as one person we looked up into the sky. As we stood there, on the corner of Duane and Greenwich, the school a block and a half away, a plane approached overhead.

“Are planes allowed to fly that low in Manhattan?” I shouted.

“No! And he’s headed straight ahead! How can he not see where he’s going?”

“He still has time to turn!” I shouted, as I strained to see what was to the right of what we now refer to as “the North Tower” or “Building Number 1” but what in those days was known by us locals simply as “the World Trade Center.” We hardly thought about there being two buildings.

“He’s not turning! Oh my God!”

And then I experienced a trick of perception that I thought about only later. First, time slowed down as I watched the airplane simply park itself into the building, high above our heads. In my perception of that moment, there was no sound. Despite the enormous, overwhelming, ear-crushing explosion that was occurring before me, in my world, everything was silent. The airplane simply silently parked itself into the side of the building. And then there were flames.

“The school!” Jen and I screamed together. As we looked toward the school, the several city blocks that separated it from the World Trade Center telescoped into nothingness. There was just the shower of flames, and directly below, our school.

We ran, she awkwardly pulling and pushing the stroller. “Oh my God, Oh my God,” we panted over and over. We reached the school; the schoolyard with its red door was empty, the gate locked. We went to the big kids’ front door. Parents were shouting and pushing. The president of the PTA, also on his first full day of school, blocked the entrance. “Now hold on, the fire department is coming. Everything will be taken care of. The safest place for your children is in this school building.”

“Get the f***k out of my way, I need my daughter,” I said quietly, and he just as quietly stepped aside. We rushed inside, looking for our children in a building we weren’t very familiar with, had visited only a couple of times. “Where are the kindergarten rooms?” I asked some poor teacher who looked completely shell-shocked. “Avery is right in there,” she said immediately, although I didn’t recognize her. I went in. There were other parents there and a frantic rush to find our children.

Then a realization swept me. I was the adult. I was the parent. I was not with peers with whom I could share my fear. I was the one who had to look in control, calm and adult. It was the first and possibly only truly rational thought I ever had, during the events of September 11.

“Hi, Avery, there’s been an accident outside and we’re going home. Where’s Cici? She can come with us,” and then there was Cici’s father John, so we grabbed the girls and their lunchboxes and headed downstairs to the exit. Once in the round brick rotunda that held the welcome desk, however, we felt wracked with indecision, so many parents and children, crowding the small space. “Should we leave? Or would it just be better to leave things normal?” we all wondered aloud in various ways. Then came a terrible sound, both deafening and eerily muffled by the round brick room in which we crowded. “What the hell…?” We all looked at each other with an indescribable combination of fear, dread, unknowing, and yet knowing. The second building had been hit, by what, we did not know.

“We’re getting out of here,” I said and I carried Avery out. Instantly I realized I needed to walk a certain way, to hold her head against my shoulder a certain way so that she could not see whatever was happening behind the school, in those buildings four blocks away. We emerged into the perfect blue-sky day to find parents frantically shaking cellphones which no longer worked (I did not even have a cell phone in those days), parents crying, holding onto each other, parents vomiting into the curbs. I walked as quickly as I could toward home, three blocks away, uptown, away from the World Trade Center.

We arrived at home in silence, Avery somehow having divined not to ask questions. It was the first of the many moments after that day that she showed the sensitivity and maturity that have become the hallmarks of her personality.

We sat, Cici’s mother Kathleen and I, on the bench inside our apartment, holding the girls’ lunchboxes, then putting them down, then holding each other’s hands. There was nothing to say. The girls themselves ran off to play, a bit confused as to the shortened school day, but happy to be together.

Finally I said, “Do you remember that time at dinner once, when we all wondered where the top of the spire of the building would land, if it crashed down sideways?”

“Yes.”

“And we found out it would crash right through our bedroom windows.”

“Yes.”

The elevator opened into our apartment and there was John, panting, sweating. “I saw the second plane go in from Times Square, and got a cab down to 14th Street, then ran home from there.” It was about 40 blocks. Kathleen’s husband John arrived and the two men went up to the building’s roof, while Kathleen and I took the girls up to her apartment, the sixth and top floor of our building, and sat silently together. Suddenly John and John shouted from the roof, “Oh my God, the building is going. We’re getting out of here.” We grabbed the children — Cici and Avery and Cici’s little brother Noah — and rode down together in the elevator, emerging into the ridiculous sunshine to head uptown as fast as we reasonably could. A young lady emerged from nowhere, holding a baby. “I came out of our building holding the baby and now they won’t let me back in! I need his food, and diapers! I have no money, no house keys, nothing!” “Come with us,” we all said, and scooped them up.

We walked, walked, walked until we came to Cici’s father’s office building on Canal Street, and rode up in the elevator to his newspaper offices, which were teeming with reporters, this sort of thing being their raison d’etre, however horrifying at the time. Everyone was on computers, on the phone, shouting, gesticulating. We came in holding the kids and headed toward an empty conference room, unconsciously, I think, looking for a room in the center of the building, not at the perimeters. The room was decorated with a photograph of the 1930s Manhattan skyline, dominated by the Empire State Building, looking down to a low, flat downtown. “We’re back there, now, if the second building falls down,” Kathleen said.

And it did. John was outside in the dust, having begged me to let him go down to the site and help. I shouted, “No! Your place is here with us!” I simply could not contemplate his going down to the site. I hadn’t even begun to worry about the air quality, what he would breathe in if he went. It just seemed unbearably tenuous and unknown to let him go. So he didn’t. To this day, every anniversary, he expresses his doubts about staying with us, about not helping. But I could not let him go down there. So he was out buying diapers and baby formula for the strange baby and lady in our midst, when the second building fell.

I remember sticking my head out the window to look at the smoldering, smoking skyscraper one moment. The next moment when I looked, it simply wasn’t there anymore. It sounds ridiculously simplistic to say it that way, but that was how the day progressed. Buildings simply disappeared.

Then it was a blur, the rest of the day, imagining that the sky was full of other plane-weapons, imagining other targets. We heard there were seventeen missing planes, twenty missing planes. No one knew what to believe. The children played nearby, oblivious. I thought, “What were we thinking, having a child in this world? How dared we bring an innocent baby into this world.” Our thoughts and fears turned to the most basic a person can have. Months later, John and I took some sort of online survey about Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, then not really a syndrome common enough to have an acronym, PTSD. One question was, “Did you at any time during your experience fear for your life?” It seemed unbelievable that such ordinary, unremarkable people as we, on a blue-sky day in Tribeca, could answer, “Yes.”

John successfully battled his way down to our apartment that afternoon, past the guards, the police and the military, and let himself in to immediately hear the buzzer, over and over. There were policement and firemen who had survived, desperately seeking water, a bathroom, a moment of peace. My mother remembers our telling her that one fireman took a long drink of water, looked around our untouched apartment and said, “Bamboo. I’ve always wanted to do a floor in bamboo… I can’t believe I’m talking about your floor, on a day like today.” “We have to try to talk about things like that,” John assured him. “That’s life.”

John came back up to get us on Canal Street and we all came home, crowding into our apartment because, being me, there was food. Everyone in the building came, all five floors of us, plus the Lady and the Baby, as I think of them now. And at some point in the evening, her husband appeared in the elevator, having walked all the way from LaGuardia airport where he was stranded. They went home. The rest of us stayed, eating meatloaf, ribs, cream of something soup, whatever we had in the fridge. And on that night, around our dining table, was born my most powerful amulet against the overwhelming fear, the existential fear, that had been created that day. Whatever happened, it would be better if “everyone” were together. From then on, I think, I’ve felt better the more people were gathered around my table.

That night no one, none of the adults, could sleep. Because we had not let her see what was happening behind her school, because intermittently for various power reasons we had no television or computer (and for some time after that, we deliberately kept her away from the television), Avery was completely sheltered from what was occurring outside her door. Our street was the first above the disaster that retained electric power. And so we stayed, through the unspeakable night of the 11th. I moved from our bedroom to the living room where I lay on the sofa, contemplating the unfathomable wound in our beloved city, our cherished neighborhood, the loss of our security, the loss of our school, the near-loss of my child, as I saw it.

The next day we all tried to live. I remember speaking to my best friend Alyssa on the phone; she was cleaning out Annabelle’s closet. Why on earth are you bothering, I thought. We won’t be alive long enough for you to care. Later that morning I received an unbelievable telephone call. A dear friend of mine who had worked as art curator for Cantor Fitzgerald, whose dead accounted for 25% of those lost, had been delayed in going to work on September 11. Her alarm didn’t go off. She was still here, still with us. Somehow her being saved only frightened me more; the randomness was almost the worst. “You won’t believe this,” she told me, “but a totally intact memo from Cantor just floated into my backyard.” She lived in Brooklyn.

The neighborhood showed the scars. An empty space where the buildings had been just blocks from our house. I described it to Avery as “a big mess you’ll see at the end of the street, but they’ll clean it up.”

Our poor old local McDonald’s.

Our poor old local McDonald’s.

And boxes of fruit covered in that toxic, memory-and identity-laden dust we could not contemplate, simply had to live with.

And boxes of fruit covered in that toxic, memory-and identity-laden dust we could not contemplate, simply had to live with.

I do not do well sleepless. By the morning of the 13th it was clear that me sleepless was not viable, and at the same time, our beloved friends Livia and Janice in New Jersey had been begging for us to come. I called Alyssa, since we did not have a car.

“We are heading out to Seacaucus, so pack up those crazy cats and come with us.”

It was the work of a moment to pack the crazy cats up, throw some of Avery’s belongings in a suitcase, and head to Alyssa’s, two blocks up. We squished everyone into her car, and drove toward the George Washington Bridge, passing an extraordinary sight: hundreds of people, just ordinary people, lining the divider between the uptown and down lanes of the West Side Highway. They faced the lane going downtown, toward the site, and held up hand-lettered signs reading “You’re our heroes, FDNY!” “FIREMEN ARE ANGELS” “GOD BLESS THE USA”.

Alyssa’s dysfunctional dog Sidney cowered on the floor of the front seat. We all rode in silence, not looking behind us. Then as we crossed the George Washington Bridge, we could not help ourselves. We turned around.

The black and gray swirling cloud caused by the falling of the two towers, palpable on some terrible Richter Scale, visible from the Hubble Space telescope, loomed in the distance downtown.

“Where is our city? Where is our neighborhood? What has happened to us?” We all asked everything at the same time.

And at that very moment, every cat in the back of the car chose to behave as if there were a litterbox back there.

“Whew! Oh my goodness…” and then Sidney’s snout, too fearful to rise above seat level normally, appeared like a little submarine spotter. “What on earth are those cats doing?” It was a moment of hilarity we all needed, to survive. And yet when our car passed by groups of men playing golf in the New Jersey sunshine, I was so angry I could hardly breathe. How dared they? Now I wonder if I dreamed that memory. Was anyone in the tri-state area really playing golf on September 13?

We arrived at Livia’s and Janice’s house and simply collapsed in their arms. Never had their pristine, white, perfect house in New Jersey seemed such a sanctuary. We stayed until September 15. I spoke on the telephone often with our families in the Midwest who were worried about us. Avery riffled through Livia’s childhood closets to find the dolls she always played with there. We drank far too much Scotch, stayed up until the wee hours of the morning, trying to make sense of what had happened. Livia sat on the edge of my bed the first night, stroking my hand. “I think our world is ended, Livvie,” I said. She held me. “It will come out all right, you know. It always does.” After a decent sleep, I felt better, but the resumed airplane flights overhead after the several days’ quiet did not help. Other people celebrated the return of planes to the sky as a sign that normal life was returning. After my experience, planes in the sky did not feel normal. Even now, I have an instinctive drawing-back when I hear or see or feel an airplane overhead. I am quite certain that that reaction will last all my life.

On September 15 we went home. The neighborhood had pulled together, as we shortly realized was just in our neighborhood’s nature. I will never again live in a place of such human warmth, generosity and common love. We had two Rocco’s: Rocco of our beloved Bazzini’s, the ancient nut and coffee company on our corner, put up a lovely sign saying many simple, reassuring things, among them, “We will rise above this and emerge stronger and closer than ever.” Rocco of our beloved “Roc” Restaurant simply brought his kitchen out to the sidewalk and fed us all, firemen, policemen, newspeople. Those of us who knew him who lived there in our streets with his restaurant, paid everything we had on us, in thanks for the love and sustenance.

On September 19, a week and a day after the events, Avery went back to school. Her school, our beloved PS 234, had been requisitioned by FEMA and was occupied not with schoolchildren but with boxes of size 11 boots and firecoats, clipboards and rapid-response telecommunications units of some kind. We prepared Avery for the “new school” which was in fact going to be a very old school, PS 41, already overcrowded and now set to welcome an extra 50% of students from the evacuated students from all over lower Manhattan.

Before we took her to school, I sat Avery down and asked her what she knew about what had happened. For better or worse, our joint parental decision had been to keep the television off, no newspapers, magazines, and no discussion of what had happened until she was in bed. But we could not let her go to school with both her old classmates and dozens of new, strange children, with no knowledge of the events.

Avery, with her characteristic intense dignity and personal reticence, even at just four years old, said, “I know the World Trade Center is gone, because you told me. What happened to it?”

“A plane flew into it and started a huge fire, and then it collapsed. Now they’re cleaning it all up before they can build something new there.”

A pause, then Avery said, “But weren’t there TWO buildings?”

“Yes. And there were two planes.”

Another pause, then she said, frowning, “That begins to sound like not an accident.”

“No, it wasn’t an accident. Some very evil people who were told to hate our country flew the planes into the buildings deliberately.”

“Why would anyone hate our country?”

“Because we are very free to do and say what we please, and we are happy and successful. That makes some people very angry and some of those people decided to hurt us.”

“I think it’s just terrible,” Avery said with the finality of the young. “I bet some people died.”

“Yes, some people did. But the whole world is sorry for us and most of the people in the world think our country is very good. And we must concentrate on that.”

If I had been anxious about dropping her off at school 8 days before, my anxiety level was now at a completely unlivable level. I had the crazy idea that the terrorists has targeted our neighborhood, possibly our school, and the World Trade Center was only a convenient place to park the airplanes. What if they followed us to the new school? As we waited outside to let the children in, I felt a fear inside me that I simply could not believe was real. We had dressed Avery in her Fourth of July dress, too small but still sweet. It had a small American flag smocked in the front.

She seemed far too small and vulnerable to be left alone at yet another school.

Her hair ribbons were red, white and blue check.

It seemed unbelievable to me that I was meant to leave her there, a block from the hospital where the victims’ families had expected to find their wounded loved ones and had left endless row upon row of identification posters.

It seemed unbelievable to me that I was meant to leave her there, a block from the hospital where the victims’ families had expected to find their wounded loved ones and had left endless row upon row of identification posters.

We walked our children into the impossibly crowded school with harried teachers running to and fro. Avery seemed fine about being there, and I was at least mature enough to realize that whatever problems there were about leaving her there were mine, not hers, so John went to work and I left the classroom, wandered out into the hallway. There I literally ran into the school psychologist, Dr Bruce Arnold, whose job had surely become about 1000% percent more difficult than he had expected on September 10. “I think there’s something wrong with me, Dr Arnold,” I said, trying unsuccessfully not to begin crying. “I really don’t want to leave her here.”

“There isn’t anything wrong with you that isn’t wrong with all of us,” he said. “And you don’t have to leave. Stay as long as you like.”

In the end I simply sat in the school cafeteria with other parents who didn’t feel like leaving, and John told me later that he got as far as the front steps of the school and then sat down and cried. It was very hard work being “normal.”

We struggled through the days being “normal” for Avery, cooking and eating and chatting and taking her to dance class. Our school was moved once more, in October, to share a sweet — but tiny — school called St Bernard’s in the West Village, where at least instead of 75 children per class there were 45. Yet another “first day of school.” They began to seem endless and I felt flattened by the pressure to get past the security cordons that isolated downtown, to get Avery uptown in time for school to begin, try to fill my day, then get uptown to bring her home. The school put up a temporary welcome “label” for us, and the beloved bronze frog that used to sit at the front door of the real PS 234 came with us, for the duration.

Often Kathleen, Cici’s mother, and I walked home together in the mornings, discovering that we felt much the same: reluctant to go down into the subway, but unwilling NOT to go down into the subway, worried about the air we were breathing at home but unwilling to join the militant group of parents who were certain we were all signing our death warrants by staying downtown.

Oh, those terrible endless meetings in the dark cafeteria at St Bernard’s, listening to perfectly normal people turn loopy and hostile, accusing other parents of being criminally negligent for even THINKING we would ever return to PS 234 and its toxic air. And yet these same parents picked up their kids every day at St Bernard’s and went home to their apartments just as close to the site as the school was. No one was rational. We all seemed to find our own ways both to be crazy, and to cope. Ish.

The anthrax threats came. We toyed with the idea of stockpiling things: antibiotics, duct tape, water. It all seemed so ludicrous, so rash and random and life-threateningly silly that in the end we did nothing. And because life goes on, Avery’s November birthday came and both our sets of parents came too, to support New York and us, to get in an airplane and defy fear.

Avery was in her element, surrounded by the girls she had played with since she was born, confident and seemingly untouched by anything that had happened to her.

Avery was in her element, surrounded by the girls she had played with since she was born, confident and seemingly untouched by anything that had happened to her.

There were balloons, carried home as always from the Balloon Saloon by John’s dad, only this time just buying balloons was tantamount to a political act. “Thank you SO MUCH for coming and buying your balloons again this year. We are really struggling here,” said the plump and funny owner of the shop. Everything we bought, we bought downtown, trying to save our neighborhood.

There were balloons, carried home as always from the Balloon Saloon by John’s dad, only this time just buying balloons was tantamount to a political act. “Thank you SO MUCH for coming and buying your balloons again this year. We are really struggling here,” said the plump and funny owner of the shop. Everything we bought, we bought downtown, trying to save our neighborhood.

Rocco came, bearing a little fuchsia beaded purse for Avery. Rocco who had been so wise, one afternoon as I stood on the corner where his restaurant was, looking down at the school, past the FEMA emergency boundary tape. He put his arm around me and said firmly, “You aren’t doing anyone any good standing here feeling sad, Kristen. It will all turn out all right. Go home. Go home and be a mommy.”

Rocco came, bearing a little fuchsia beaded purse for Avery. Rocco who had been so wise, one afternoon as I stood on the corner where his restaurant was, looking down at the school, past the FEMA emergency boundary tape. He put his arm around me and said firmly, “You aren’t doing anyone any good standing here feeling sad, Kristen. It will all turn out all right. Go home. Go home and be a mommy.”

We began to recover, bit by bit. I cried every day, at some point in the day, or at many points in the day, for months. Everything seemed, as one of my favorite authors once wrote, “like the last train leaving the station.” Every morning when I dropped Avery off at school, I imagined never seeing her again, expected never to see her again, and every afternoon at pickup I felt my life had been saved. The most lasting legacy of September 11 for me is that a bit of this feeling has lingered to this day; saying goodbye to my daughter and saying hello again will always feel apocalyptic to me.

We began to recover, bit by bit. I cried every day, at some point in the day, or at many points in the day, for months. Everything seemed, as one of my favorite authors once wrote, “like the last train leaving the station.” Every morning when I dropped Avery off at school, I imagined never seeing her again, expected never to see her again, and every afternoon at pickup I felt my life had been saved. The most lasting legacy of September 11 for me is that a bit of this feeling has lingered to this day; saying goodbye to my daughter and saying hello again will always feel apocalyptic to me.

While it’s all well and good to live each day as if it could be your last, it’s exhausting. It’s not normal. Human life depends on a certain casualness of spirit, sometimes, and that element of our lives was missing for a very long time, after September 11, 2001. For me, it would require going back to PS 234 to become normal again…

And we did. Follow us here.

Kirsten, I had no idea this happened to you and your family since it happened before we reconnected on FB. We all have our vivid memories of that day and the aftermath, but I don’t know anyone else who was an eyewitness. This has been an emotional time for so many of us. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Kristen, I enjoyed reading this blog. I could relate on so many levels except having such a young child. I also had the experience of watching the first plane fly over head and into the building. You and I were about a block apart heading north. I too have no memory of sound from the moment the plane struck the building until we were safely at a friends husband photo studio in Soho. That included seeing the second plane “park” itself in the other tower, running to my husband office on Broadway with Madeline saying “we’re going to die” and my saying we were not!!! Through streets with emergency vehicles who must have had sirens. No sounds did I hear when the first building came down and we saw the smoke coming up Broadway. Very odd reaction indeed and you are the first person who said they too lost their hearing. Of course we could hear our daughters but that was it for me. Thanks for sharing your story with such honesty. We are all forever connected by that day. XOLoretta

Jennifer and Loretta: thank you for your comments. I love you both from the past, and treasure your reactions to my memories.

Hello old friend, I just read this again. So incredible what we all went through. Sending love on Sept 11, 2022. The years archon

Love, Loretta

So powerfully and beautifully written. Utterly compelling, Kristen. I simply cannot imagine but your words bring home the awful magnitude of those horrific events. As the mother of a small child, it’s unthinkable. Sending love.